Violet Peters (nee Philips)

Interviewed by Trish Levido on 12 September 2006

Tape 1 – Track 1

Trish Levido. What is your full name and why were you named it?

Violet Peters. Violet May Peters, my mother called me Violet, she nearly called me Daisy and I said, ‘well just as well you didn’t because I would have had to change it’.

Trish Levido. And you had no nickname when you were growing up. Where were you born and when?

Violet Peters. I was born 16th December 1917 in Middlesex England.

Trish Levido. You are of particular interest to the library because you grew up in what we call the soldier settlement. What do you remember and what was the address?

Violet Peters. 15 Central Avenue Mosman, I was about two then.

Trish Levido. Was the house already built when your parents took you there?

Violet Peters. Yes and my father cemented all the paths.

Trish Levido. The paths leading down from the street?

Violet Peters. Yes, back and front, our house was in the middle of the block and there was a big frontage. We had a beautiful garden of flowers, orchids, dahlias and a vegetable garden down the front.

Trish Levido. That block of land went all the way from Central Avenue down to Bay Street.

Violet Peters. The back entrance was in Central Avenue and the front was in Bay Street. There was a lovely green weatherboard house in the middle which my husband maintained until he died.

Trish Levido. What can you tell me about living in Central Avenue?

Violet Peters. It was quite unique really – Beauty Point. Apart from the houses which had been built for us the whole place was bush at the front and everywhere.

Trish Levido. Was Bay Street a road?

Violet Peters. No, we had a dirt track down the front of Bay Street.

Trish Levido. And that dirt track came off Spit Road did it?

Violet Peters. No, we’re down the front in Bay Street at the water. Up the back – there were practically no houses there in Central Avenue and Medusa Street. Where the little school is in Medusa Street there was no school, it was all bush as well. I used to spend my childhood running around in the bush in both those streets. I used to leave my shoes on the land where the school now is in Medusa Street and I had to be sent back to look for them, but Mosman was a great place. Bay Street was just a track back and front, until a road was built. Up the back at the Central Avenue end there were none of those houses next to Mrs. Scott. We used to go up a track because the dairy was up there at the bottom of Medusa Street and I had to take a billy and go up to the dairy to get milk.

Trish Levido. When you say at the top of Medusa, do you mean….

Violet Peters. …..at the bottom of Medusa Street..

Trish Levido. ….where Medusa Street joins Spit Road, that’s where the dairy was?

Violet Peters. No, it’s down Bay Street end?

Trish Levido. Down Beauty Point end, down towards Middle Harbour?

Violet Peters. No, that little hill where the Scott’s house was, just at the top there.

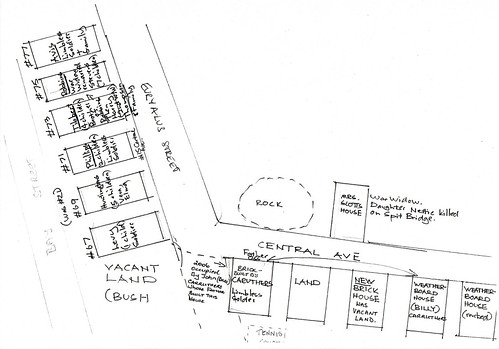

Trish Levido. Together with this tape recording we’re going to put in a drawing of the houses because it gets very confusing after a while, working out where all the different houses are and where everybody lives.

Trish Levido. OK, so we’ve got you growing up here, of your earliest memories how many people were living in the houses around you?

Violet Peters. Plenty of children; Aunt Avis up the top which is number 77 now. There was a mother and father living with a soldier and two boys and a girl – three children.

Trish Levido. He was a limbless soldier was he?

Violet Peters. Mr. Avis, yes, and then Mrs. Robins, she was a war widow but she remarried a man named Stevens. She already had five Robins’ children but then they had two girls so there were seven there.

Trish Levido. Tibbett?

Violet Peters. They were there for only a very short time, they had about four kids, there was a big difference in ages with the husband being away for six years.

Trish Levido. Wait a minute we’re moving too far into future. Go back to when you were a child. You’re growing up there.

Violet Peters. There were only two, my sister, and I and we went to Mosman Public School.

Trish Levido. How did you get to school?

Violet Peters. We walked from home.

Trish Levido. All the way to Mosman Public to where it is now?

Violet Peters. I walked everywhere, all my life.

Trish Levido. Was the school where it is now?

Violet Peters. Yes

Trish Levido. Mosman Public School was where it is now and you walked from your house in Bay St to school.

Violet Peters. Of course, and we picked flowers in Bapaume Road and brought them home to our mother everyday – we stole flowers.

Trish Levido. Tell me about Huntington’s house.

Violet Peters. They were next door there were four girls and one boy who all went to Mosman School as well.

Trish Levido. They had five children too, what about Levy?

Violet Peters. Only one down there.

Trish Levido. Then we come round into Central Avenue and we have the house of the Carruther’s.

Violet Peters. Well they had three children, John, Peter and Margaret.

Trish Levido. And then we had a block of land and then we have the new brick house where there’s more land.

Violet Peters. There was Mrs. Scott up on the….

Trish Levido. …..we haven’t got to the weatherboard house yet, was there anybody living in the weatherboard house when you first lived in Bay Street? Billy wouldn’t have been living there then.

Violet Peters. We were the first people living in those houses.

Trish Levido. So why would Billy have been living in the weatherboard house, he couldn’t have been when you first lived there because he was 10 years younger than you.

Violet Peters. They were always up there. What year did he tell you he went into the brick house where we are now?

Trish Levido. I can’t remember I haven’t got the sheets with me.

Violet Peters. They were all up in the weatherboard house.

Trish Levido. They started in the weatherboard house then, – right OK, that’s fine. And there were three children there?

Violet Peters. Yes.

Trish Levido. So there were lots and lots and lots of children.

Violet Peters. Oh lots of children and we used to play in the streets because there was no traffic, we had billy-carts and everything. The boys used to shove the girls around in billy-carts up and down the dirt roads.

Trish Levido. Did you all play on the tennis courts or weren’t they built then?

Violet Peters. Eventually, when the tennis court was built, yes, Mrs. Avis and myself, we played tennis down there. I must tell you that our houses, after they were built – I believe they were made of excellent weather board, whether it was pine or not, I don’t know but the man that bought my house said what wonderful timber was in our houses. The verandahs back and front were not enclosed, so our mother had ours enclosed back and front.

Trish Levido. Why did she have it enclosed?

Violet Peters. Well the beds on the front verandah which were useful in coming ages after I grew up and had my son. We had a bed on the back verandah eventually too. My grandfather used to sleep there and he died there.

Trish Levido. And lots of the houses would have done the same?

Violet Peters. All built the same.

Trish Levido. And they all enclosed their verandahs like your mother did?

Violet Peters. I think they improved them, yes.

Trish Levido. They were weatherboard houses were they Vi, or bricks?

Violet Peters. Oh yes, the green weatherboard.

Trish Levido. Can you describe the house when you walked into it?

Violet Peters. Facing the harbour we had the front verandah which my parents enclosed, then coming into the house we had a bedroom each side and a long hall right down the center; a fairly large lounge and dining room and then into a very big kitchen. We never took the chimney out of that house and it had a fuel stove which we never removed it was still there when I left. There was the back verandah off that and then my father had two rooms built on the back so my sister could come up from Adelaide because she was having a difficult marriage, so it finished up having about nine or ten rooms I suppose.

Trish Levido. When you first went to the house you were two. You told me earlier that you didn’t go to school till you were seven.

Violet Peters. That’s right because it was unnecessary in those days. Our children went to Miss Langley in Mosman so I could do some work, when they were two or three, and then at four I think they went up to the other school. Children in those days didn’t have to go to school until we were seven.

Trish Levido. Do you remember doing any chores around the home before you went to school?

Violet Peters. I had a very strict father and I did shopping for my mother all my life. I’m very organised but she used to give me money – I can still remember the low price of food – she used to send me with a basket up for a leg of lamb. I’ve done shopping from when I could walk about and carry it.

Trish Levido. Where did you shop – at Spit Junction?

Violet Peters. There were some shops at Warringah Road before Spit Junction. I think it’s called Parriwi Road now. They had a good butcher shop there. I don’t remember if there was a grocer shop there. Where there’s a garage now there’s a little one, when you come out of Central Avenue there was a grocer shop there.

Trish Levido. But the grocer would have delivered wouldn’t he?

Violet Peters. No.

Trish Levido. Who came to your house? Did you have a baker?

Violet Peters. We had Mr. Joyce – maybe that was his name – with gorgeous big custard tarts, we had clothes props delivered, and a block of ice, the man used to come in and throw it into the icebox thing in the kitchen. The laundry which was outside in the yard had a fuel copper, which we never removed.

I hated Sundays, my father being a soldier, my sister, my mother and my father had to take a clothes basket, and we said, ‘we’re going down to the bush’ and he chopped wood for the copper that we had to carry it home in the clothes basket every Sunday. I think she had coke in the fuel stove.

Trish Levido. What about the Chinese gardeners, were they around?

Violet Peters. I don’t remember those.

Trish Levido. At the Parriwi shops there was a butcher and a baker.

Violet Peters. I don’t remember the other shops.

Trish Levido. Did you take your lunch to school or did you go home?

Violet Peters. I took it because it was too far.

Trish Levido. You would never have got home in time, did you run to school and back again?

Violet Peters. I’ve been a big walker all my life and I’ve walked everywhere. When my son was a baby and when I was living in Neutral Bay where the Oaks Hotel is, I used to wheel my son in the pram home to Beauty Point to see my mother on a Saturday, and then wheel it back in the afternoon and then my husband went to the war and my mother wanted us to come back home and so I went back home and that was the only time I was out of house for a short time.

Trish Levido. In your early childhood you mentioned that your father was very strict. Can you expand on your parents’ marriage, was it a happy marriage?

Violet Peters. Not particularly, it wasn’t terribly happy; he had health problems because he lost his leg in the First World War in France – Passchendaele. He had these moods and he could turn very moody at homes at times.

Trish Levido. Wasn’t he one of the Rats of Tobruk?

Violet Peters. No, that was my husband.

Trish Levido. Were you frightened of your father, or just nervous of him?

Violet Peters. I was very nervous of him. He was terribly strict but to give him is due, people would say that he was a good father. I can remember having to sit while he showed me how to read the time and do up my shoes. I was never allowed to go to bed until 8 o’clock at night, regardless of how tired I was. I was in dread of my father actually, but I used to lie down on the kitchen floor on the lino, or out on the back verandah and I was so tired I felt like going to sleep there, but he’d turn round from the kitchen table and he’d say, ‘you can go to bed now’. He was a bit cruel, so I had to go to bed then but I wasn’t allowed to go before.

Trish Levido. Have you any idea why?

Violet Peters. It was to do with his neurosis from the war. He was buried for a long time before they dug him out and put him on the stretcher to take him to the hospital with a broken leg, but they let him slip off the stretcher and it injured his leg beyond repair and he lost it. He had an artificial leg. Finally he was on a pretty good level, but he was difficult.

Trish Levido. Did you have a brother and a sister, or just a sister?

Violet Peters. Just a sister, ten years my junior.

Trish Levido. So you were born in England and then your parents came out to Australia.

Violet Peters. On the Osterly to Australia.

Trish Levido. And they brought you with them when you were two.

Violet Peters. Oh yes, my mother wouldn’t part with me, I was absolutely devoted to my mother. She was gorgeous. She was a very good looking English lady, she never lost her colour and she was lovely, but dad was a fulltime Australian.

Trish Levido. You said that he was very difficult, and your sister was born after the war?

Violet Peters. Yes, 9th October 1927 – ten years younger than me.

Trish Levido. Tell me what your favourite games were with the other children in the street.

Violet Peters. I was a terrible tomboy. I’ll never forget the first day I went to school with my little suitcase. I always liked boys, so come lunchtime I took my case and went into the boys’ playground – I’ll never forget this – and sat on the long seat with the boys. I was always in the company of boys, I loved boys. I’m not mad about groups of women, they can be very catty, I liked mixed company where you can have some sensible conversation and I still like mixed company, but I was the same from when I was seven.

Trish Levido. Did you have a bike?

Violet Peters. No because I rode one once and I fell off and I’ve still got scars on my legs from skating and falling off bikes etc.

Trish Levido. So you walked or ran to school but you never rode a bike to school?

Violet Peters. No, The Depression was on, my parents couldn’t afford things that the children have today.

Trish Levido. Tell me about The Depression, what was your life like?

Violet Peters. Well we’re going back to when I was little, even when I was in my teens up to when I was 17 – no.

Trish Levido. We’re back at school.

Violet Peters. I’m back at school – well my mother saw that I always had everything I needed, she dressed me beautifully.

Trish Levido. Did you dress in girly-type clothing even though you were a tomboy?

Violet Peters. No, they were very lovely clothes, she knew people who made clothes and crocheted – I’ve got a photo somewhere of a crocheted lemon and blue or something frock, but she dressed me beautifully.

Trish Levido. Would you say that your parents were well off after the war?

Violet Peters. Do you know that those people only paid £300 for the land and the cottage?

Trish Levido. So that was land and cottage?

Violet Peters. Yes, it took her most of her life until she died to pay it off. That’s why she wanted us to go on living at home. After Harry went to the war I put all my stuff in storage – because my husband was wonderful at maintaining the home and my father even loved him. Harry painted that place and looked after it so my dad didn’t have to do it then.

Trish Levido. So that’s what went to paying back the house.

Violet Peters. The business after she paid the house off, I suppose.

Trish Levido. For how long was she paying off the house?

Violet Peters. It took her years and years. The way money was in those days you only had to pay such a little bit off, it took most of her life to pay off the £300. I remember distinctly when she told me she’d finished paying it off. I’ve got all those papers in that file.

Trish Levido. Was £300 a good price?

Violet Peters. That sounds like a fortune, when I went to work like most people my age would tell you the same story, I got 12/6d an hour and then I was in a great position after that because I got 17/6d an hour and we slaved – I tell you. That’s why I’m so competent.

Trish Levido. So you were doing very well to get 17/6d an hour.

Violet Peters. That’s the highest yes, my word.

Trish Levido. That must have been a week Vi.

Violet Peters. It was a week.

Trish Levido. So you would have got 17/6d a week not an hour. Tell me about the house, your mother was pleased to have the house? Were there a lot of houses around at that time?

Violet Peters. Only our weatherboards – about nine or ten; it was all bush everywhere. I heard there were Aboriginal drawings down on the waterfront on some of the rocks. I never saw any Aborigines but I heard them talking about them, that they had been there, maybe they moved out when we moved in. We probably scared them out.

Trish Levido. I would say so; tell me about the man that lived in a cave.

Violet Peters. I remember seeing him walking up the beach. He had a long beard and a big topcoat and bag slung over his shoulder. He was there for years.

Trish Levido. Do you think he came home from the war and lived in the cave?

Violet Peters. I don’t know. He might have just been a drop-out and never recovered from the war. I think he was found dead in that cave.

Trish Levido. Where is the cave?

Violet Peters. It’s down behind where Billy lives down on the water’s edge.

Trish Levido. Below where the tennis court was, below Bay Street. On the water’s edge there’s a cave and he lived in there?

Violet Peters. Yes, he was there all the time when I was little.

Trish Levido. Were you frightened of him?

Violet Peters. I just kept on the opposite side of the street. Nobody was scared of him, he wasn’t abusive, I never heard him speak, but the kids must have given him a terrible time. Vera Huntington and Alma – Vera told me the other day – she was born in 1921 in the house next door to me, and I was in that house before they came there, so they’re just down the road now, if ever you want to speak to Vera or Alma, they live next door to each other. We grew up together and we’re still friends.

Trish Levido. So all the children would play after school in the bush every afternoon?

Violet Peters. Yes, on the dirt roads, not in the bush.

Trish Levido. That’s on Central Avenue and Medusa Street, back and front.

Violet Peters. Going up and straight into the dairy.

Trish Levido. Was the dairy very big, was it a big dairy?

Violet Peters. No, it’s down the lane where the Beauty Point bus goes down Medusa Street. When you get out there’s a lane, the house on that corner at the dairy was where that house is, we could see the other end of it down where I lived. We used to go up the track with the billy can to get milk.

Trish Levido. He would have delivered milk to everyone in your area?

Violet Peters. We had milk delivered, yes, we had everything, we had ice and milk and custard tarts.

Trish Levido. And your mother grew vegetables?

Track 2

Violet Peters. We had the most magnificent Christmas bush tree where Bay Street is now on the water and cars used to stop to look at that tree. Harry used to take it down to the Mosman Medical Center at Christmas to Doctor Huntley and they used to take it to the hospitals and all that. That’s when we got the wonderful gardens.

Harry was an expert gardener all his life and my eldest daughter is the same, she lives just over the road, that’s why I have to be near where she is, I’m not allowed to be by myself in case I have a turn, which I have had occasionally, but yes we had a great vegetable garden down one side of the front and Hugh could tell you that we had the most beautiful garden, we had prize dahlias that came from his dad’s garden at Neutral Bay. We had prize orchids, a lot of them which came from Doctor Huntley’s garden. I had to have a garden and I was by myself there for 10 years after Harry died, he lived to 66.

Trish Levido. Can we go back to when you were a child?

Violet Peters. We didn’t have a garden then my father was not a gardener, Mr. Huntington from next door put in a narrow path going right down.

Trish Levido. What did your father do after the war?

Violet Peters. He was a lift driver in the city, a manual type of lift, he could do that.

Trish Levido. He could pull the lift up and down do you remember where he was working?

Violet Peters. In one of the big stores in the city I can’t remember which one. It was in the middle of the city where are lot of the big shops were.

Trish Levido. And he continued to be a lift driver until he died, how old was he when he died?

Violet Peters. 63, and he worked right up to when he died. He had heart trouble and he died in the car at the wheel on Glebe Bridge or somewhere. He was dead before a bus hit him and cut the car in half just about. I’ve got a picture of that too.

Trish Levido. Why is there such a discrepancy in the names, why is he called Wainwright Philips?

Violet Peters. The same as with my mother, there was a bible that my father’s mother gave to him when he went to the First World War. I think that’s the name his mother had put on the bible.

Trish Levido. Wainwright or Philips?

Violet Peters. James, Wainwright Percival Philips. My daughter-in-law has had all the trouble in the world in London trying to get through registrars. She thinks she’s got the right person but my mother’s got herself down as Florence Rosetta. In those days it wasn’t terrible important you could readily change your name. I think it’s because everything was so lax you know. From when we went to school we had to write our correct name. Both mum and dad seemed to have fiddled theirs a bit.

Trish Levido. Can you tell me anything about this plaque? What is your earliest memory of it?

Violet Peters. When I walked from the front verandah to the harbour, there were three or four stone steps going down to the front garden, it was placed by the side of the steps.

Trish Levido. Why was it there?

Violet Peters. I don’t know you’d have to ask the stonemason or the builder. It was attached to the house you see before the garden was put in.

Trish Levido. Because it says, ‘Private J.W. Philips’…..

Violet Peters. ….the plaques were on the foundations of the cottages.

Trish Levido. So every single house had one of these plaques.

Violet Peters. I think each one where there was a returned soldier. Huntington’s have got one in their home. They called their house ‘Perone’ and I think that’s the name on their stone. Don and Robin live there now, theirs is the only weatherboard still there, and they’ve put planting around it.

Trish Levido. Is theirs number 21 Bay Street?

Violet Peters. I was 71 they must be 69.

Trish Levido. What’s their last name?

Violet Peters. Huntington’s were there. I knew they had a stone, but Don and Robin excavated and had rooms underneath for their two children, whether they still put the plaque on their wall I don’t know, but we were interested in asking where they were keeping the plaque and the young man who has since worked there, he said that certainly it is there. They put it down in the front they knocked down the wonderful (phone)….

Trish Levido. Were these special houses when they were built in any way, seeing they were built by the Voluntary Workers Association?

Violet Peters. They just loved all the soldiers, they had been to war and came back and they’ve done their bit and they were limbless.

Trish Levido. Do you know anything about anybody else in the houses, were they all limbless, or were they war widows?

Violet Peters. Two of the war widows remarried men here.

Trish Levido. Vi, we start off with number 77 Bay Street which was Avis.

Violet Peters. He was a limbless soldier.

Trish Levido. That was him, his wife and children?

Violet Peters. Yes, his original wife with two boys, and a girl.

Trish Levido. Then we move to the next house along which was the………..

Violet Peters. …..Mrs. Robins, she was a war widow, her husband was killed in the First World War, and she had five children. She married Mr. Stephens who was not a returned man at all and they had two children. Tibbett’s were in there for a short time, he was the brother of Mrs. Robins and somehow or other she got him that house, the family paid rent and they were gone again.

Trish Levido. Who was in the house after the Tibbett’s?

Violet Peters. Harry and Edna Thompson, they did away with the end of the house looking over the harbour and he had half bricked that, he was going to do the whole cottage. He was not a returned man. He served in the Air Force for a short time during the last war.

Trish Levido. So your father was a limbless soldier.

Violet Peters. Harry my husband was a Rat of Tobruk he was away for six years.

Trish Levido. That was the limbless soldier and then again your husband was in the war. Let’s move to the Huntington house.

Violet Peters. He was a returned soldier, he was wounded at I think at (indistinct) Peronne because that’s what they called the house. They were there practically as long as I was in mine because Vera was born in 1921 in that house next door to me. They were first in there too. I was first in there by a few months I think.

Trish Levido. Levy – they had one child, was he a returned serviceman?

Violet Peters. Yes he was a returned man but his wife, she was a Mrs. Carter first of all and she was a war widow from the First World War, and then she met Levy. He was a widower and they had this little Jewish girl. He was a returned man and he had a damaged heart. Her first husband never came back from the war.

Trish Levido. Then we move around the corner to Central Avenue and in the house we’ve got Billy Carruther’s dad?

Violet Peters. He was a limbless soldier too.

Trish Levido. Then we’ve got a block of land and then we’ve got the weatherboard house. Who was living in that house?

Violet Peters. Billy hasn’t lived in that brick house for too many years I can tell you.

Trish Levido. You mean in his father’s house?

Violet Peters. Yes, it was his father’s house.

Trish Levido. Who was living in the weatherboard house before Billy?

Violet Peters. There was the man and the mother and the two children, Billy and Margaret.

Trish Levido. They were in the weatherboard house first.

Violet Peters. Yes with their legless father.

Trish Levido. So they started off in that house and then they moved down to the corner later on when he sold the weatherboard house.

Violet Peters. They came back down to my places….

Trish Levido. …..towards your houses?

Violet Peters. Yes, he’s built this big brick one.

Trish Levido. That was just land before he built that wasn’t it? OK, was there anybody on other side of where Billy lived? Who was in the other weatherboard house?

Violet Peters. There were two weatherboard houses but I don’t know the people – they were obviously renting because people used to come and go in those two, I didn’t know them at all.

Trish Levido. So this was rented out? OK. What was the biggest occupation that you would say the children loved doing when you were going to school? What was the favourite thing you did?

Violet Peters. We were a team of tomboys. The boys made billy-carts, there were no main roads back or front, we had the dirt tracks and we used to just – some of them had bikes but they made billy-carts – there was not much money for toys.

Trish Levido. What did you do?

Violet Peters. I took part in everything.

Trish Levido. Was Spit Road a road?

Violet Peters. We had trams of course that came up Parriwi Road. I was speaking about that to my son. I’ve got a brilliant son too, he’s written a book on philosophy. We were talking about the trams and we were having a laugh. I was only 20 when I had him. He’s a brilliant man, he lectures at Massey University.

Trams: yes we used to go down Macquarie steps, my sister and I used to go to Manly every Saturday afternoon it was always a favourite place for me. We used to catch the tram and go down. He told me the date that the bridge was built, and there used to be a punt that we used to get across there and get the tram and go to Manly, my sister and I, every Saturday day afternoon.

Trish Levido. From what age?

Violet Peters. I was in my teens, I was married at 19 – in my teens and she was 10 years younger, but we used to always catch the trams to Manly.

Trish Levido. Tell me about leaving school. You left when you were how old?

Violet Peters. Just 14 and everybody was only earning – people still talk about The Depression and we all had to get to work.

Trish Levido. Did your father have a legacy from the war – he was on the full pension.

Violet Peters. When I was married at 19, to speak about the prices of everything because the currency hadn’t changed then, but I had a little cane basket and I could fill that up from the greengrocer, they allowed eight shillings a week for all the fruit and vegetables and I used to carry this great basket.

Trish Levido. What was the first job you got?

Violet Peters. That was the Manly job because I learn everything fast and she had learnt to cook at a cooking class, so she taught me to cook as well and I looked after the baby. This was in Mosman in Warringah Road.

Trish Levido. So she needed somebody to help look after him.

Violet Peters. Yes, and I think this Adrian Brown who speaks so beautifully and follows the war everywhere, he is the son of the Adrian Brown that I had to look after and take out everyday and all that.

Trish Levido. Why were you doing that? Was the mother working, did she not have a husband?

Violet Peters. I had no training and there was no money to send me to business college. I was not terribly educated, my daughter is Director of Education now at Tafe, but that’s not the best job, she’s a retired Industrial Officer. She was 28 years up at (indistinct). But the people in the Commonwealth Bank, the wonderful Charlotte at the bank – you see I’m excellent with money etc, so I said to her one day, ‘I’m not as educated as my children’, she said, ‘being clever with money has nothing to do with education, you’ve either got it or you haven’t’. I managed money better than my clever daughter.

Trish Levido. Why were you employed to look after the little boy? Why didn’t the mother look after him?

Violet Peters. Because she was a socialite – that’s the answer.

Trish Levido. I didn’t understand what she was doing all day long so that she needed you to look after her son.

Violet Peters. I won’t name names, but I know all the socialites of Sydney, I know everybody, I’ve done work for them and I’ve done their parties and I’ve done everything for them.

Trish Levido. How did you meet your husband?

Violet Peters. Alma Huntington and I were walking up to Spit Junction on a Friday night and he was standing up there – we say it was love at first sight. He was standing there with another fellow with a football blazer on. You’re not going to believe this but he was eating peanuts out of a big shopping….. (laughter). He was such a good looking young man, but young people in those days were so responsible. A fellow at 19 was a man, not into all this nonsense that kids get into today.

Trish Levido. Was the war on when you met him? What year did you meet him?

Violet Peters. We knew the other one in the blazer and we stopped to speak. He was a football coach. He introduced Harry to us and so that’s how we met.

Trish Levido. Was he in the armed forced then?

Violet Peters. Oh no, he used to do gardening and he worked at the big ‘Boronia’ next door to the Spit Junction Hotel. He had all that greenery in beautiful flowers.

Trish Levido. He was a landscape gardener?

Violet Peters. Yes and he did that and there was another big Jewish family near the Zoo, so he split the work between the two places as a gardener. He’s terribly patriotic he has a wonderful war service; he’s a terribly brave person. When the war started my son was 18 months and he went straight away and volunteered and went into the Army.

He went all through the Middle East then to New Guinea where they shouldn’t have gone after they came back from the Middle East and Tobruk. They were too weak and sick to stand up and they were sent up to New Guinea and being so sick he got malaria. He was in hospital in New Guinea for about eight months. I didn’t know if he was dead or alive because no mail could come, he was in a dangerous state. When he came back home he was de-mobbed.

In the meantime my daughter was born. I fell pregnant when he came back on the ships from the Middle East so he never saw my daughter until she was close to one or two. She was so shocked when she saw a man in the house at Beauty Point when he came home. She must have been more than one because she ran up and screamed – no that’s another occasion, she just screamed the whole time. I held her in the kitchen while he was trying to talk to my mother and me and she screamed her head off, just looking at him. She’s him to a T, even to look at, and she’s the great gardener too.

Trish Levido. Vi, lets go back a little. When you first got married where did you live?

Violet Peters. Neutral Bay, close to the Oaks Hotel, in rooms.

Trish Levido. And you stayed in those rooms until the war broke out and your husband left to go overseas. And then you went back to live in Bay Street.

Violet Peters. Yes got my things out of storage – the bit of furniture that we had.

Trish Levido. And you went back to Bay Street to live with your parents.

Violet Peters. Yes, and I stayed there forever then.

Trish Levido. Your father was still at home when the Second World War on, he stayed home the whole time because he wasn’t able to work, or was he still working as a lift driver?

Violet Peters. He was working as a lift driver during the Second World War. When my father was in the Army and when he came back with an artificial leg they taught him to do shoe mending but he didn’t like that so he gave that away and then went to work as a lift driver.

Trish Levido. When you went back to live in the house, was that when your parents enclosed the verandah?

Violet Peters. No, they did that long before I went home, that must have been done when I was single.

Trish Levido. But you didn’t sleep on the verandah did you?

Violet Peters. No, but my son did after we went back.

Trish Levido. So during the war you’re living in the house, your husband comes back from the Middle East and then he goes to New Guinea.

Violet Peters. Yes, in hospital the whole time when he was there.

Trish Levido. And you were pregnant with your daughter. So when your husband came back from the war, ill with malaria…..

Violet Peters. …..malaria stays with them for years and years, it never leaves their system.

Trish Levido. So he was sick and he was sent home, he was de-mobbed.

Violet Peters. Well the war had ended then.

Trish Levido. So he served all the way through to the end of the war?

Violet Peters. Yes.

Trish Levido. Was he ever a prisoner?

Violet Peters. No, he was terribly lucky. He was moved out of the 8th Division and put into the 9th. He said had he stayed in 8th he would not have survived being a prisoner of war, the Japs. His mother and I were amazed when he came home and said that he had been accepted as A1 into the Army in the first place because – well he’d been smoking since he was about 10 and he already had all these chest troubles. They were so hard up for people to send to serve in the war…..

Trish Levido. ….they’d take anybody.

Violet Peters. They did.

Trish Levido. When he came home you continued to stay in the house in Bay Street.

Violet Peters. Yes, I suggested to my mother that we move out but my dad was already dead and she couldn’t have managed that place by herself. My husband has kept that place a picture because he was a tremendous worker, and he painted it. The one next door number 69 where Don and Robin lived, it’s the only one that hasn’t been – the McCloud’s, they lived in number 69 next to me on the lower side. They put cladding all around theirs, but they remember Harry telling me, ‘whatever you do, don’t put cladding around the weatherboard house because you’ll never know what’s underneath’, so that’s why our house was never clad, but he painted it. The McCloud’s is still up and it’s got the cladding all around it.

Trish Levido. Do you mean where the Levy’s were or where the Tibbett’s were.

Violet Peters. No, the lower side.

Tape 2 – Track 1

This is Trish Levido and I’m taping for the Mosman Library on the 12th September 2006. Vi is telling us about her husband returning from the war when she was living in number 71 Bay Street with her mother. Her father had subsequently died and she’s living in 71 Bay Street with her husband who had returned from the war and her son and her daughter.

Trish Levido. So your husband painted the house throughout, did he get a job after the war?

Violet Peters. Oh yes, at the Water Board, and he got to be a Chief Inspector. I’ve got a wonderful letter from the Water Board. He went close to the top and he did very well and I missed him a lot. I told you I had two children, but I’ve got a younger daughter.

Trish Levido. We haven’t talked about her yet, but at the moment we’ve just got you with the two children, your son and your daughter and then?

Violet Peters. I’ve got a beautiful younger daughter.

Trish Levido. And she was born in the house too, all the children were born in the house, did you have a midwife or a doctor to deliver them?

Violet Peters. I had my three children at the North Shore Hospital. Mrs. Huntington had all her children in the house.

Trish Levido. Would you say, looking back Vi that you were all middle-class children? Would you say that any of you were considered to be any better or worse than anybody else?

Violet Peters. Oh no.

Trish Levido. Everyone was the same.

Violet Peters. Everybody speaks very highly of me. I can deal with all people no matter who they are, and Beth and I traveled a lot – Elizabeth, my eldest daughter. We traveled until I was grounded. My doctor told me last week that I have a great understanding of all people. I’ve looked after elderly people – I love elderly people and I love children. I’m not too keen on the middle lot at the moment. But I get on well with everybody.

Trish Levido. What I’m trying to establish is whether these houses were considered to be Mosman houses of the same standard as the rest of Mosman, or did you ever feel you were looked down upon?

Violet Peters. Well the rest of Mosman wasn’t there but they’re all in now, what we call the nouveau yuppies.

Trish Levido. So none of these houses were built down there when you were living there? You had this long gap, if I talk you on a walk through your mind and you were leaving Spit Junction and you were walking down towards your home what was there? You said there was a group of shops at Parriwi Road.

Violet Peters. A lot of units have been built along the roads now, all the old homes were knocked down.

Trish Levido. So there were old homes there.

Violet Peters. There was the very wealthy Purcell’s living on the corner of Awaba Street, walking up. They were very wealthy people.

Trish Levido. But what were they when you used to go school at Mosman, they were just little timber cottages were they?

Violet Peters. I can’t remember now whether they were timber or brick. Down the Spit, if I’m coming on the bus to Manly just where all the fish restaurants are, there was a heap of weatherboard cottages down there, the people we knew used to wave from their gates to us.

Trish Levido. Were they built before or after the war?

Violet Peters. Must have been before, Harry had a family of friends who lived at the Spit.

Trish Levido. Was it a wealthy area or not in those days?

Violet Peters. I think they built all that part – what I call recently.

Trish Levido. So you continued to live in the house with Harry after the war and you had the three children and your mother was alive to when?

Violet Peters. I nursed my mother and my husband for 13 years, nine years with her, and then four with Harry. Doctor Huntley said he doesn’t know how my beautiful mother lived that long, but it’s because of the care she had with myself and the Mosman Nursing Sisters coming in. She had pancreatic cancer so she died at home and then I had Harry for a few more years. He then took a sudden stroke the week he was to have the great farewell party at the North Sydney Anzac Club from the Water Board, and the whole place was booked out.

Trish Levido. That was going to be his retirement

Violet Peters. …..his retirement – this happens to a lot of men and he had a major stroke I was back and forth to hospital and because they knew that I could do that, he was allowed to come home with brain damage, but I tell you when he died he still had more brains then any of us. The Nursing Sisters loved him, he was such a good patient, and so was my mother. When she died I had him for a few years and then I looked after him for four years at home. So I had 13 years where I couldn’t look up off the ground. I had to rush up the street to do shopping, and leave him sitting in a chair and wondering whether I was going to find him lying on the floor, I had to get a cab back to be quick.

Trish Levido. He didn’t come back from the war with any bad memories like your father did?

Violet Peters. I know a lot about how Harry behaved in Tobruk. One of his best mates came back on leave when Harry was still over there and he told me Harry was so fearless. If he did, he never – having seen so many people killed in front of him, he came back with a different attitude to my father. He never spoke about the war. The ones who had been through the worst of it never do. Dick Apnell said that in Tobruk when they were being bombed and they all went down underground, he said Harry was a fatalist, he wouldn’t go down he just used to lie on the ground and cover himself with a blanket and stay up top.

Trish Levido. In other words he wouldn’t go down to the trenches.

Violet Peters. Someone said he should have got another medal because he was so brave in Tobruk. He was a transport driver and he used to go behind the lines at night and steal stuff from the enemy and bring it back to the people.

Trish Levido. You were very lucky to have such a lovely husband.

Violet Peters. Yes and my daughter is him to a T, she has a wonderful nature.

Trish Levido. Do you have any grandchildren?

Violet Peters. My dear – I have 14 great grandchildren now, and I’ll have 15 in another month. My son went to live in Campbelltown after they were married and they had seven sons, so now they’ve got all these grandchildren and there’s five or six girls. Betty, my eldest daughter didn’t have any children, but Denise my youngest daughter had four and now she’s got Joshua and she’s got a little baby who will be one in another week, So I have 15 – thank goodness they’re all in Campbelltown..

Trish Levido. Do you ever get to see them?

Violet Peters. Oh yes, we’re invited to all their birthdays and we had wonderful Christmases at Beauty Point.

Trish Levido. Tell me about the Christmases.

Violet Peters. This is the only time I miss Beauty Point, I’ve never been homesick for Beauty Point.

Trish Levido. Before we get on to Christmases at Beauty Point, when did you leave Beauty Point?

Violet Peters. 1st September 1994 I came here.

Trish Levido. And that was because of your health.

Violet Peters. No, I couldn’t keep the house going any longer. I kept it going for ten years. I only had $2000 left to my name and I couldn’t get anybody to come and paint the place.

Trish Levido. You sold Beauty Point and moved here.

Violet Peters. I could seat 30 people in that dining room at this table at Beauty Point. Christmas and Boxing Day were two big days and I was shopping and cooking for about three weeks. I had a table in the big kitchen and another table on the back verandah and I had garden furniture everywhere. There were over 30 of us adults with Harry’s lot. Elizabeth loved Christmas, she was married at one stage, but she’s happily divorced.

Trish Levido. Which one is she?

Violet Peters. Elizabeth, she’s my middle daughter that lives nearby to come at night if anything happened to me. I had all my family on Christmas Day because my mother being English you can imagine what Christmas – people always did all the cooking at home, so one night I can remember we didn’t eat Christmas dinner until midnight because of the heat wave.

Trish Levido. You had a fuel stove.

Violet Peters. No, on the gas stove, we didn’t cook on the fuel stove. When I was a kid we had it going. My sister and I used to cook toast on it and have a bit of fun. But Christmas and Boxing Day was huge at Beauty Point, then the Campbelltown lot came up –all of us and then they came on Boxing Day, but the two days were full. I never get used to the smaller space, I can’t entertain here, so Christmas is always a bit nostalgic because I can’t do anything in this place it’s not big enough. My son’s family, take it in turns at Campbelltown now to have Christmas. But they all agree it’s nothing like mine was because I’m a better cook.

I love to cook, but if I cook here I’ve got washing up to do so I’m inclined to eat out a lot. I go to Terrigal to the hotel there, I’ve been used to staying in this place for six weeks at a time, I’ve been going there for 20 years now. I stay in room 206 they give me the same apartment all the time in the Hotel Terrigal. And they all love me. I’m going up in October for five days because you see I’ve got to get back to the water, I always had the view at home.

Trish Levido. And that’s what you miss.

Violet Peters. And the fact that I can’t entertain here and cook.

Trish Levido. It says here on the back of the sheet that the library has about the stone plaque at 71 Bay Street Mosman. Just correct this as we go along.

‘Research indicated that the stone plaque at 71 Bay Street commemorates the building of cottages to house World War One Returned Soldiers, it appears that these cottages were built on land owned by Voluntary Workers Association Mosman branch’.

Did you know any of the other volunteer workers in the Association who built the house?

Violet Peters. No, I was only just a baby out from England. I know a lady in Mosman named Selfe, I can’t remember her first name, and she mentioned that Jack Selfe her brother worked for Harry at the Water Board. She said that her uncle or somebody in the Mosman Selfe family was one of the voluntary workers on the houses. He was working with the voluntary workers. I think there’s an ‘e’ on the end of their Selfe name. Bonny Selfe, I don’t if she’s dead or alive.

Trish Levido. Am I correct in assuming that these voluntary workers were returned servicemen who built these houses for other….

Violet Peters. …..no, they couldn’t be returned servicemen. I doubt that they would have been strong enough to build those houses.

Trish Levido. So these were just other younger men who built the houses.

Violet Peters. I would say so, but I wasn’t on the earth at that time.

Trish Levido. ‘The owners of the houses were most probably returned soldiers, as a check of the Australian War Memorial First World War nominal role indicates.’ That is correct because we have now gone through and we have a list of who those people were and most of them were related to the war.

Violet Peters. I think the two or three that came there when I was tiny were given those houses, I think they were living in the bush and they’re the ones that only stayed there for a few weeks and left.

Trish Levido. They didn’t like it because it was too far away from everything else. It says here:

‘The role of Private J.W. Philips is not clear; he may have been the Philips who attended the Mosman/Neutral Bay Rifle Club’. He never did belong to the Rifle Club did he?Violet Peters. Not in my lifetime, not since after the First War, but supposing they were a family – he and his mother, father and sisters lived at Cremorne Junction. He could have belonged there, this could only have happened before he went to the war, and before he met my mother. He could have been in the Mosman/Neutral Bay Rifle Club.

Violet Peters. He could have been.

‘He may have been the Philips who attended the Mosman/Neutral Bay Rifle Club meeting in 1918 when a request was made by a Mr. Philips for assistance in building the cottages at Quakers Bay’.

Would 1918 be the right time for him to request that with your mother?

Violet Peters. What happened there, I found that out from my father’s eldest sister May she worked as a young lady, her family named De Putron at Clifford Street and she is the one who asked them could they see that her brother got one of the houses.

Trish Levido. And that’s how you came to be there.

Violet Peters. Aunty May worked for the De Putron’s and she requested….

Trish Levido. …..she would have heard that he was going to build these houses.

Violet Peters. That’s right, she must have.

Trish Levido. And then she came home and told her parents and your father would have said that he wanted one of those houses to live in. Did she live in one of them too?

Violet Peters. Oh no, they lived in Parraween Street at Cremorne.

Trish Levido. So she never lived there.

Violet Peters. Oh no – no way. It was through another who remained for a short time.

Trish Levido. How did you find that out?

Violet Peters. I’m trying to think how I did. It might have been through my daughter-in-law looking through the records of everything. She’s putting together a pretty good family tree.

Trish Levido. ‘Suggestions have been made by present day residents that Bay Street was the site of a hospital for disabled soldiers and a site of a psychiatric hospital for returned servicemen’.

Did you ever know anything about that?

Violet Peters. No, I never heard anything about that.

Trish Levido. ‘Based on the research it is more likely that Bay Street was the site selected to build accommodation for returned soldiers. The house at 73 Bay Street is a renovated weatherboard which maybe one of the original weatherboard cottages’

Now we can say it was one of the original cottages. Was there any changes ever made to the houses in the time that you lived there, other than enclosing the verandahs?

Violet Peters. No, they remained the same until sold or knocked down. John is very unhappy about certain ones – people buying them and tearing them down…..

Trish Levido. …..and building other houses on the block. Why was Mrs. Scott’s house separate to the other houses?

Violet Peters. Possibly there wasn’t the room down there, she’s on a lump of rock just up by my back gate, there’s a bit of a rise of rock. Her house is sitting on top of that.

Trish Levido. So she would have been looking over the top of your house.

Violet Peters. She’s looking down into my backyard and into our kitchen area.

I haven’t seen it, I don’t go around Beauty Point at all because I don’t like those allotments, they’re up and down the coast everywhere you go it appeared at Queensland and down the other way. I think they’re spoiling the look of all the waterfronts, but that’s only my view.

My eldest has a block over there, she said Beauty Point was one of the most beautiful places in the world, and we’ve been everywhere because we love the hot weather, the boats, and the heat, but I’ve been grounded.

Trish Levido. When you were growing up Vi, did you find that the trees weren’t as thick as they are now on Beauty Point, because John Carruthers showed me some photos of his house and he said that there were quite open spaces where they could have picnics and the trees weren’t very thick.

Violet Peters. My son when he visited recently looked over the top and he’s amazed and upset. He feels that Billy is living in a matchbox there now, selling all the bits of land and he’s stuck there in a matchbox. Probably that one on the waterside knocked his view out. Marge…..

Violet Peters. You could know her but she’s so envious of me living in a unit. Because he’s an armchair (?) man and she’s got to go back and forth to see Helen (?) and you can’t shift him, he won’t move.

Trish Levido. Why did his father buy all these houses – this land?

Violet Peters. A wise, wise move because buying them for that price….

Trish Levido. …..but where did he get the money from?

Violet Peters. My mother paid £300 for the house and land and look what they’re going for now. We have a man in that big block over there whose a good example of this. He’s bought the two bottom units which would cost Margaret more than well over a million for the two – over $600,000 each. He was talking to me one day – oh and he owns another place up the lane here, but he said that his father bought blocks of land at the time for £50 at Lane Cove and then they sold them and this man has got, money, money, money. But Billy’s father wouldn’t have paid the whole £300.

Track 2

Trish Levido. How do you pronounce his name, de Putron I think it’s a French name. Why was he involved in it, do you know anything about him?

Violet Peters. No, because we weren’t here then.

Trish Levido. ‘The architect was William de Putron a resident of Clifford Street Mosman. We have no idea why he chose…..’

Violet Peters. Harry’s sister worked in the house as a maid.

Trish Levido. Right, so that’s how come we’ve got the connection and why he ended up there.

Violet Peters. This is interesting isn’t it? You also said that the house that James Philips was living in was called ‘The Ferns’ and I asked mum where she got the name from and she said that was the name of a big home she worked for in London as a domestic – where you wore aprons and caps and all that; and I had to wear all that as well when I was a nanny for the lady.

Trish Levido. Tell about Beauty Point and why it was so beautiful?

Violet Peters. Well the view looking down to the water, that’s why I go to Terrigal regularly – to get back to the water.

Trish Levido. Tell me about the Castle.

Violet Peters. It was criminal to pull that down, it had turrets, and on the grounds were great tiles.

Trish Levido. When was it built?

Violet Peters. I don’t know it seemed to be there forever. That was sold before I left Beauty Point and pulled down and something horrible built.

Trish Levido. Was that built when you were a child?

Violet Peters. It could have been, but I wouldn’t have been interested in looking at buildings when I was little. But what is vivid in my mind about my house on the front verandah before it was enclosed – when they first attempted to build a house down the front in the bush they got part of it up and somebody burnt it down. I can remember leaning on the rail on the front verandah and we watched that place burn down. Somebody must have decided they were not going to have any houses around about, so when it was half built they burnt it down.

Trish Levido. Is this on the other side of Bay Street?

Violet Peters. Straight down where Billy lives now – just down in the bush.

Trish Levido. Was it kids that burnt it down?

Violet Peters. Oh no, all the kids would have been in bed. We don’t know who burnt it down.

Trish Levido. Did you ever go out with any of your neighbours?

Violet Peters. I feel that the Huntington’s girls were like my sisters, I was an only child until I was 10. We’re very close they live down the road at the foot of Griffiths Street, and then there’s Condamine they both now live in the two-storied places and they’re almost as old as me. Shortly they won’t be able to climb the stairs. Alma is in one and Vera is in the other, they often ask me for lunch, but I can’t walk too much.

Trish Levido. Were they tomboys too?

Violet Peters. Up to a point, they used to follow me, and I was always a great actress and we used put on concerts and I was always the star of course.

Trish Levido. Where did you put the concerts on?

Violet Peters. In our own houses on the front verandah, I was always a bit of a comedian I used to go to shows in the Town Hall, do a bit of dancing with the Mosman Musical Society.

Trish Levido. Do you remember going to the pictures?

Violet Peters. I can remember going from when I was so little and they had to put the seat up so I could sit on the top. I can remember as time went by I grew taller and I was able to sit on the seat. At home I had a mark on the wall between the kitchen and the back verandah and I was so impressed to see how tall I was growing.

Trish Levido. Did your father had a car, was that one of the few cars, or was there a lot of cars?

Violet Peters. We had an old Ford at first and then my parents bought a new Chev, and he died in the big old Chrysler that Doctor Huntley would have died himself if he knew dad had it with his bad heart. He used to leave it in Mosman around the corner when he went in to see the doctor, and the doctor had a fit when he saw the photo of the car cut in half and my father dead in the front of it.

Trish Levido. Did you go away for holidays?

Violet Peters. Yes, we used to go camping up near Terrigal a lot.

Trish Levido. Did you like that?

Violet Peters. Yes, and when I lived at Beauty Point Mrs. Levy had a cousin who was a driver of one of the tug boats and on the weekend – don’t ask me how – but he used to be able to take all of us in these houses on the tug boat all around the harbour and everywhere.

Trish Levido. Up to Parramatta?

Violet Peters. Yes, all over the place. We’d go to the parks and have lunch and get back on the boat. I can remember sitting up on the nose of this tug coming back in the dark and I’m sitting up on the end with my legs hanging over; Mrs. Levy used to bring a teapot that was about this big.

Trish Levido. And she’d boil the billy?

Violet Peters. We did all these things. It’s been a great life you know, it’s different now but I’ve still got a good life.

Trish Levido. Is there anything else we haven’t covered?

Violet Peters. I wanted to have a rave to you about the view down there. More and more boats were coming, this was happening at Beauty Point when I left there 12 years ago. I never wanted a boat.

Trish Levido. You never wanted to go on a boat?

Violet Peters. Well we’ve been on some wild rides up on the islands on the boats, but I never wanted to own one.

Trish Levido. When you were a child John Carruthers said that he built boats out of gal iron etc.

Violet Peters. He might have, but I only went on the tug, oh and up the islands with Beth. I tell you one thing that I think of in the night sometimes – I never forgot about Beauty Point from when I was little. In that bedroom up on this side there’s the harbour. Late in the night a fishing boat used to come back home and go up to Cammeray and I can always hear that chug-chug of it in the night, so I’d know what time it was – close to midnight or something. I used to look out and I could see the lights on it, and it moored right up the top near Cammeray. Bob Hawke lived opposite my place you know. He still lives there. And then there was the Zoo that came down to the water and it had kangaroos that used to be running up and down. Well Bob Hawke’s place is just nearby.

Trish Levido. Do you mean the Taronga Zoo?

Violet Peters. No, there was a private place at Beauty Point over at North Bridge right opposite my place and it used to have this steep run down to the water’s edge and there’d be these animals running up and down.

I said to Billy – I jumped up and down and I said, ‘good, I’ve been hoping somebody over all these years would ask me about Beauty Point and how wonderful it was’, and he said, ‘don’t you ever come down to see it now?’ I said, ‘no, I have no desire to see it now’.

They’ve put two houses on my block which should have had one in the middle and then all this lovely land. The first one that’s in Central Avenue is a tall thing I believe. Marie Perry tells me, she lives next door to where Mrs. Scotts would have been and she said it’s got a pool that’s big enough to swim and back in, and then he’s got the other big one jammed on to Shorebutt’s place.

My husband built the most wonderful brick wall it took him 18 months to build it and of course they’ve knocked it down. Can you imagine though, the space from here to the unit next door with that railing, I believe they’ve put – this man’s that’s bought the one next door with the pool – there’s two garages underneath. It has had God knows how many different renovations in the 12 years since I left. With the garages down there how can he get his cars out of there? Nobody can get the cars out of there because of the railings, and there’s a steady line of one-way traffic. You couldn’t possibly get your car out. Our garage was at the back.

Trish Levido. Up on Central Avenue where it should have been.

Violet Peters. The lassie from the big Central Avenue halfway up the hill – a beautiful girl nearly 21, with long golden hair, she got killed there.

Trish Levido. What’s the difference between big Central Avenue and little Central Avenue?

Violet Peters. Only because outside my back gate was a dirt track but then the other road was already cemented.

Trish Levido. You mean close up on to the main Spit Road.

Violet Peters. Her parents had one of these Combi vans and I saw her cleaning it – no she was still at school so she was probably about 17. She cleaned the car in the afternoon and then her mother asked her to come down around our places and down Bay Street just to go to that local store on the main Spit Road, but being so young they think she swerved to avoid a dog and she went through the railing and landed upside down. So she got killed there, the road is so narrow. How could a man with a brain think he could get his car out with the rail over there? I think it has changed hands a few times since I left.

Trish Levido. Is there anything else?

Track 3

Trish Levido: I’ll finish off the tape now. Just repeat that again.

Violet Peters. I think that the house at Beauty Point had served its good purpose. It served my father a First World War soldier and then my husband who had a very distinguished service in The Second World War for being a Rat of Tobruk – six years away.

Trish Levido. So they did the right thing by building the houses for the returned servicemen.

Violet Peters. Absolutely right. But they did away with all that beautiful bush, building so close together and it’s happening everywhere.

Trish Levido. We’ll finish up now, but do you remember having the school built in Medusa Street?

Violet Peters. It wasn’t too long ago before the Shorebutt’s came there.

Trish Levido. Which house did they live in?

Violet Peters. Next door to me.

Trish Levido. Were they in the Tibbett’s or the Huntington’s house?

Violet Peters. The Tibbett’s.

END OF INTERVIEW